Globally, it is estimated that 58 million people live with chronic hepatitis C (HCV), with 1.5 million new infections occurring each year.

The blood-borne pathogen is most frequently spread through sharing needles or other equipment used to inject drugs, or through exposure to contaminated blood during medical procedures.

The hepatitis C virus can produce inflammation which may over time lead to scarring of the liver tissue (fibrosis), liver failure and liver cancer. While there is no vaccine for hepatitis C, treatment with direct-acting antiviral (DAA) therapy can cure the infection in more than 95% of cases. However, in many areas, and for certain populations, access to diagnosis and treatment remains low.

Given the high morbidity and mortality attributed to HCV, the World Health Organization (WHO) set a goal of eliminating the virus as a public health threat by 2030. This goal, launched in 2016, is now part of the WHO’s broader Global Health Sector Strategy on Viral Hepatitis, HIV and Sexually Transmitted Infections.

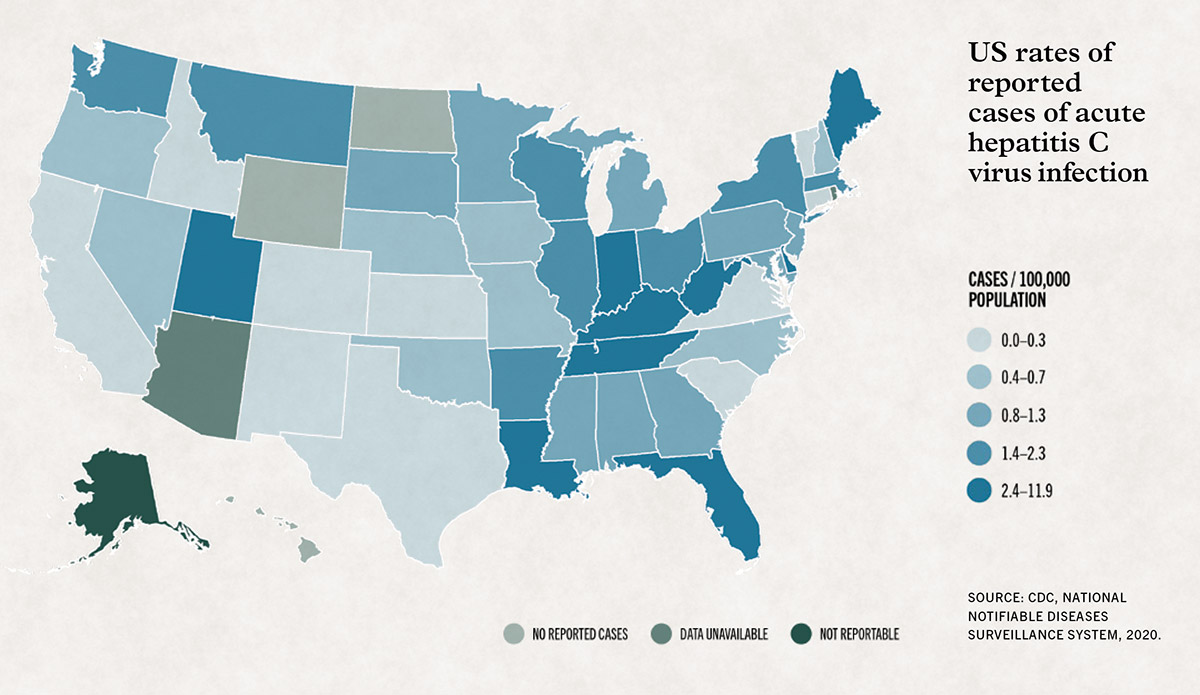

While significant progress has been made since 2016, the COVID-19 pandemic presented a tremendous setback for HCV elimination initiatives around the world. Currently, the U.S. is not counted among the 11 countries on track to meet the WHO goal, despite committing themselves to it at the World Health Assembly in May 2016. However, infectious disease experts at CUNY SPH believe that New York City is well positioned to eliminate hepatitis C as a public health threat by 2030.

Dr. Jeffrey V. Lazarus, who joined CUNY SPH as professor of global health in January 2023, has on-the-ground experience in viral hepatitis elimination efforts in multiple European and African countries, including from the decade he spent working at WHO.

“There are estimates of over 90,000 people living with hepatitis C in NYC,” he says. “That’s a lot of people. But I have a good idea of what’s possible and what the barriers are. I think hep C elimination is absolutely possible in the world by 2030, and in NYC much faster—particularly among certain populations and particularly in our hospitals.”

Estimates indicate that over 1% of people treated in emergency rooms in New York City have hepatitis C.

“Improving testing in ERs, as well as among other populations who are already in our care is a good place to start,” Lazarus continues. “For example, if you have HIV and are on antiretrovirals and being treated in a hospital in NYC and haven’t been tested for hep C, that’s a problem that we can address. A multi-pronged elimination plan can start in our hospitals by asking a series of questions, like ‘should anyone pass through our hospital system with undetected hepatitis C?’ I think most health care providers would say ‘No.’ ”

Professor Lazarus’ proposed strategy of addressing HCV infections in hospitals is an example of the micro-elimination approach that he developed while serving as vice-chairman of the board of the EASL International Liver Foundation. The approach focuses on particular populations, particular geographies, or sometimes a particular population within a particular geography.

“We launched the micro-elimination approach in 2017,” he explains. “It was really a response to countries saying it was going to be too complicated to eliminate hep C, and too expensive. So, we said, ‘Well, we need to start somewhere, so let’s focus on those with the highest prevalence.’ ”

Taking a micro-elimination approach doesn’t mean giving up on the broader goal of elimination. Lazarus says the ability to clearly demonstrate small successes is useful for generating the political momentum needed to eliminate the virus at a larger scale.

“We have incredibly effective drugs that cure more than 95% of the people who receive them,” he says. “The tools are there. It’s a matter of political will. The micro-elimination approach is a strategy to focus on small wins—and this can be particularly helpful in mobilizing hospital administrators and political leaders.”

Moving out of the hospital and into the community, a micro-elimination approach entails focusing efforts and resources on populations already identified as having a high prevalence of HCV.

Dr. Pedro Mateu-Gelabert, a sociologist and associate professor of community health and social sciences at CUNY SPH, has been working with precisely such populations for over 25 years. An expert on opioid use among youth, he works on multiple interdisciplinary research projects focused on HIV and hepatitis C prevention among people who inject drugs (PWID) in New York, Puerto Rico, Colombia and across Latin America.

Mateu-Gelabert has sat on several committees on hepatitis C elimination organized by New York state government. Like Lazarus, he is optimistic about the prospects of eliminating the virus.

“Not only New York City but New York State has the goal of hep C elimination and I think that’s very commendable, and the plan is very aware of the necessity of specifically addressing hep C among people who inject drugs,” he says.

Dr. Mateu-Gelabert highlights the importance of increasing access to behavior change programs and harm reduction services across New York State to prevent new HCV infections among PWID overall, and specifically emphasizes the need to focus on those between the ages of 18 and 29.

“Young PWID are becoming the new repository for hep C,” he says. “We need to facilitate and expand access to behavior change programs and harm reduction services that are more geared towards young people. Currently harm reduction programs are not fully reaching young people.”

One such innovative behavior change program geared towards young PWID is the Staying Safe (Ssafe) Intervention: Preventing HCV Among Youth Opioid Injectors. Mateu-Gelabert and Research Associate Professor Honoria Guarino are co-principal investigators of the ongoing NIDA funded research project.

Ssafe is based on four years of research among PWID in areas of high HCV prevalence to find out how some individuals remain virus free.

“After years of injection, there are some very proactive aspects to [some PWID’s] behavior that leads to them preventing hep C in a place where most people get it,” Mateu-Gelabert explains. “So, we did that research for a good four years and then I decided to package the content of this investigation, all those extremely savvy practices, and turn them into an intervention.”

The intervention consists of five sessions of 2.5 hours each, in which participants are provided with practical knowledge about HCV and overdose prevention. In addition, Ssafe participants have access to a mobile app.

“We created this app as a support system for young people, and now we’ve realized that it has huge potential to reach PWID across areas of the United States and the rest of the world where they are stigmatized, where harm reduction doesn’t reach or is prohibited by law,” Mateu-Gelabert says.

This innovative digital tool, which in its early stages is already reaching PWID in 15 states, is an example of the kind of decentralized healthcare services that can break down persistent barriers to HCV diagnosis and treatment posed by geographic isolation or social stigma.

Pedro Mateu-Gelabert

Jeffrey Lazarus

Barriers to elimination?

Both Lazarus and Mateu-Gelabert acknowledge that while eliminating HCV in New York City is feasible, it will be neither simple nor easy. Mateu-Gelabert points out that it will necessitate addressing the problem in other areas.

“New York State is not isolated,” he says. “We know there is a lot of circular migration among PWID in New York and other parts of the US and other countries. The prevalence of HCV among PWID in Puerto Rico, for example, is completely off the chart—as high as 60%. If hep C is high elsewhere, that will have an impact in New York State.”

Lazarus advises that, when thinking about elimination as a target, it’s useful to remember that it doesn’t mean zero infections. “It’s always going to be a challenge in a city where there’s a lot of turnover in the population,” he says. “But elimination doesn’t mean there are no new cases—it means pushing it down to a very low level. And once you have the system in place [to comprehensively test, diagnose and treat] it won’t be as hard to maintain, simply because there won’t be as many cases.”

Post-COVID opportunity

While COVID-19 has hindered HCV elimination efforts worldwide, it has also presented opportunities. The pandemic has highlighted the importance of investing in public health systems and led to greater recognition of the need for universal health coverage. There have also been efforts to leverage existing healthcare infrastructure to provide hepatitis C testing and treatment services alongside COVID-19 services.

“I think it’s an exciting and empowering time because the public now realizes that health-related quality of life is something they want,” says Lazarus, who recently convened 400 scientists from 100 countries to publish the Global Consensus Statement on Ending COVID-19 in the leading multidisciplinary scientific journal Nature. Lazarus sees the massive change wrought by the pandemic as an opportunity to expand the kind of decentralized healthcare services and infrastructures necessary to tackle HCV.

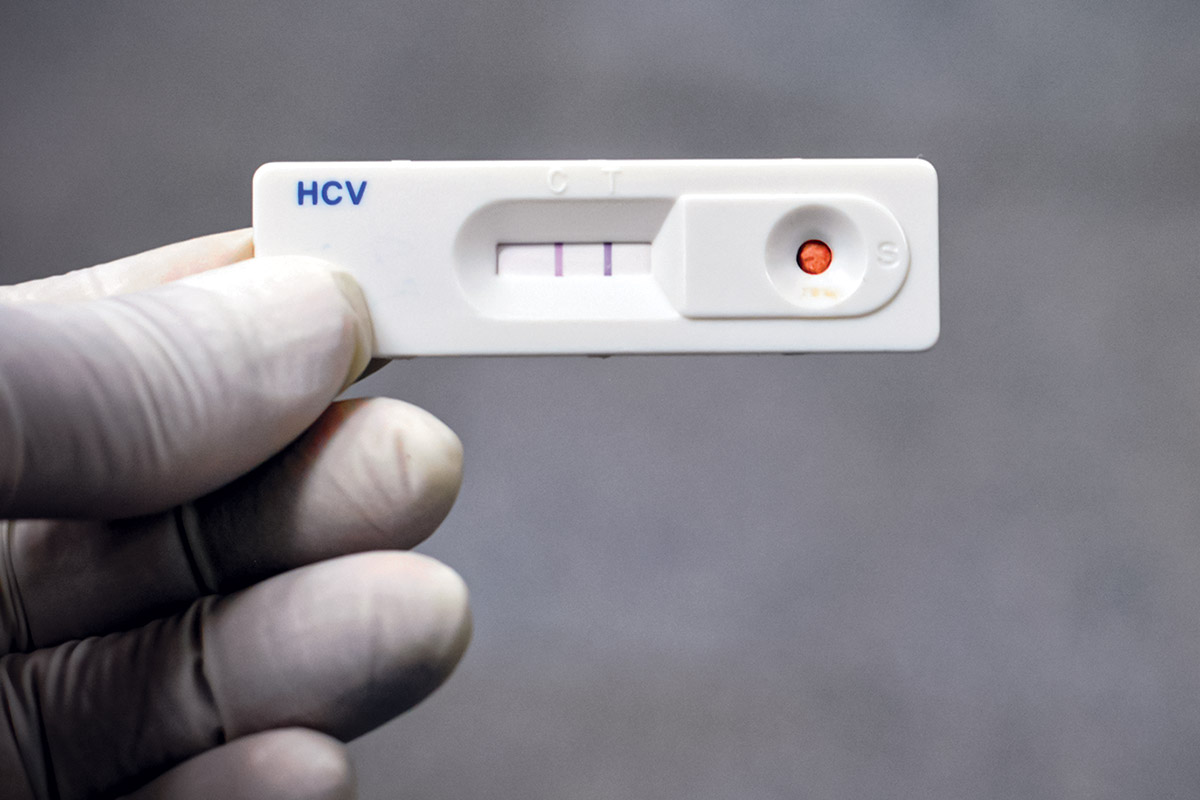

“Decentralized care is possible,” he continues. “It’s a change in thinking because we’re used to hospitals and clinics. It’s hard to walk down the street in New York and not see a rapid COVID-19 testing station. The rapid HCV antibody tests look very much like a COVID antigen test. They’re just as easy to use. We know that we could set up rapid antibody testing sites across the city. They’re cheap, so why don’t we do that for hepatitis C? That’s a political question. That’s an awareness question.”

Lazarus is new to the city and eager to collaborate with those already involved with hepatitis C elimination efforts.

“It’s exciting to be here and start meeting with the people already engaged in this,” he says. “So, I’ll be looking forward to collaboratively setting reasonable targets for the city including having the right policies in place. This is about unifying, convening, bringing people together and saying, ‘we can actually do this in NYC and set an example.’ ”

A hepatitis C rapid test showing a positive result.