Associate Professor Nasim Sabounchi, pictured in front of a causal feedback loop diagram.

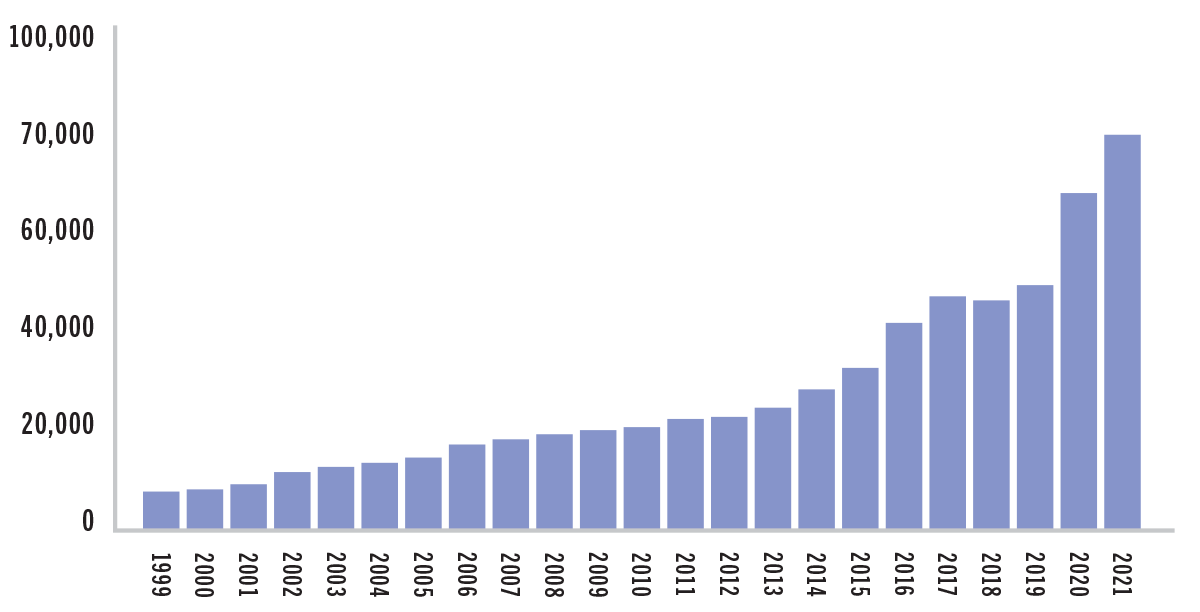

Since 1999, there has been a 400% rise in drug overdose deaths, and 70% of that increase occurred in 2019 alone. Then, in the early phase of the COVID-19 pandemic, from April 2020 to March 2021, the incidence of opioid overdose deaths increased by 32%.

That is the alarming context for a potentially game-changing research project at the CUNY SPH Center for Systems and Community Design led by its director, Professor Terry Huang, and Associate Professor Nasim Sabounchi. The team has been capturing the complexities of the opioid crisis in real time and in real communities. Their first set of findings were published in the March 2023 issue of the journal Research on Social Work Practice (Vol 33 Issue 3).

The work is part of the HEALing Communities Study, in which CUNY SPH researchers are collaborating with their counterparts at the Columbia University School of Social Work in an effort to reduce opioid overdose and deaths across 16 communities in New York. The study is part of a congressionally mandated program across 67 communities in four states (Kentucky, Massachusettes and Ohio in addition to New York) to mitigate the opioid crisis, administered by Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) and the National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA).

Representing the New York State arm of the study, Professors Huang, Sabounchi and colleagues have developed a systems science simulation model that differs sharply from the traditional, linear approach. The latter is valuable for analyzing the relationship between two single variables—say, a drop in price for a certain product and the number of units sold. But the opioid crisis is nothing if not complex. Accordingly, the CUNY system dynamics model takes into account the relationships and interdependencies between evidence-based practices, diverse community stakeholders, social determinants and, importantly, social forces such as stigma—all of which may change and interact in unforeseen ways.

“We see our model as a virtual laboratory, where different community interventions can be tested,” Huang says. “Our methodology may be generalized to other public health topics and settings. That’s the beauty of the systems science approach.”

Total National Overdose Deaths Involving Any Opioid,

Number Among All Ages, 1999 - 2021

SOURCE: CENTERS FOR DISEASE CONTROL AND PREVENTION, NATIONAL CENTER FOR HEALTH STATISTICS. MULTIPLE CAUSE OF DEATH 1999-2021 ON CDC WONDER ONLINE DATABASE, RELEASED JANUARY 2023.

The role of communities in the process

While the list of stakeholders may vary from community to community, it typically includes law enforcement, criminal justice agencies, first responders, health professionals, patient advocates, families, social service organizations, clinical sites, emergency departments, local officials and people with lived experience.

Some or all of the above were invited to join community coalitions in eight of the 16 communities in New York State during “wave one” of the study. Wave two, still underway, will focus on the eight remaining communities. Also in wave two, the researchers will shift from qualitative to quantitative modeling.

In both waves, community coalitions are the indispensable research partner and, hopefully, the ultimate beneficiary of any reduction in opioid overdose and deaths, both during the data-gathering period and after the project comes to a close. Via interviews with coalition members plus meeting notes, the research team collected the data that would inform their model and shared their discoveries regularly.

Originally, the researchers planned to go into the communities in question. That would have allowed the team to pursue a more participatory approach to systems modeling, “but COVID made that impossible,” says Associate Professor Nasim Sabounchi, the study’s first author. “However, we found other ways to solicit input from stakeholders that led to real-time revisions in the model at every step.”

“For instance, the supply of opioids changed radically with the shift from prescription opioids to heroin and, most recently, to fentanyl,” Dr. Sabounchi continues. “Fentanyl is so potent that it’s equivalent to a huge increase in supply. More deaths occurred in 2022 than in 2021, which was the worst year of the opioid epidemic thus far. That increase had everything to do with the flood of fentanyl into communities.”

As Huang explains, “Our model showed that the uptick in deaths during the pandemic would likely have happened anyway, due to the vastly greater potency of fentanyl, although a proportion of the increase in deaths is also linked to social isolation and deteriorating mental health early in the COVID pandemic.”

Evidence-based practices

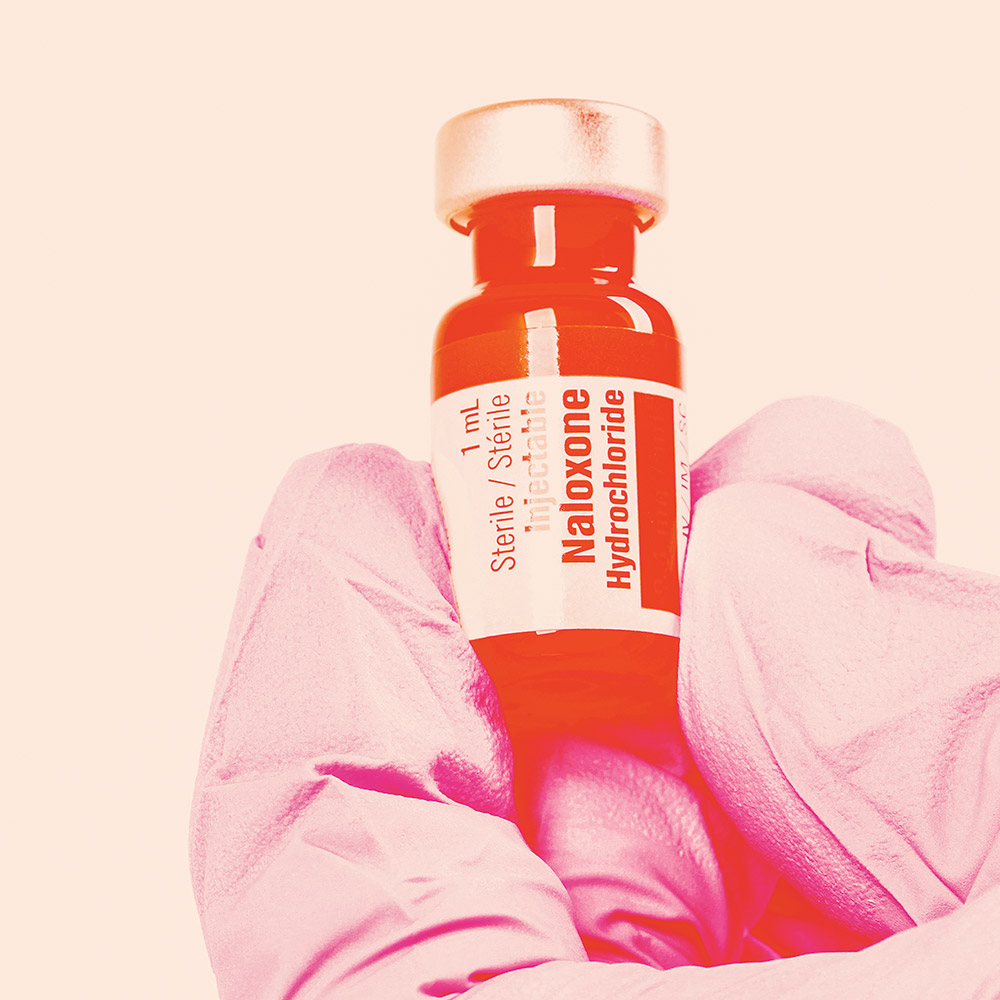

Specialists have long advocated for the three best practices used to stem the tide of unintentional overdose and death: opioid overdose education and naloxone distribution; medication treatment for opioid use disorder and safe prescribing of opioids.

What became clear to all concerned was the interconnectedness of the community system underlying the opioid crisis. A collective and cross-sectoral approach will be needed to address its complexities.

A siloed approach—one that focuses on one group or one treatment modality—is doomed to fail, the researchers say. The systems model results by the CUNY SPH team shows that in order to succeed in reducing opioid use disorder, overdose and deaths, all three of the evidence-based practices listed above need to be provided in tandem, along with much greater prevention efforts to reduce opioid exposure, as they work synergistically.

Causal feedback loops

The interrelationships between complex variables have been visualized in causal loop diagrams based on the input and collaboration of eight communities during wave one of the study.

When depicted visually, these diagrams can look like tangled webs with arrows pointing every which way. That, the researchers say, is what life looks like as well. For ease of use, the research team synthesized eight diagrams into one generalized image.

Feedback loops are extremely valuable for anticipating unintended consequences. For example, what if more people with opioid use disorder start entering treatment—a desirable outcome on the face of it—but the community has limited capacity to treat them? Should that be the case, communities might be motivated to advocate for new policies and increased funding for treatment centers.

Another feedback loop that was identified by most of the communities in wave one of the study had to do with the stigma associated with naloxone distribution. Naloxone can prevent overdose deaths but does not necessarily prevent overdose. That fly in the ointment may lead to compassion fatigue on the part of first responders and police, who may come to believe that naloxone actually encourages opioid use. And compassion fatigue in turn may increase stigma against those with opioid use disorder generally. A key finding of the model, then, has been the need to link two evidence-based practices: naloxone distribution and medication treatment for opioid use disorder. Used together, these may help to reduce compassion fatigue and its associated stigma.

Stigma, the researchers found, was a fundamental variable rather than a sideeffect of the crisis. When people with opioid use disorder are deemed unworthy of help, a community can make little progress in addressing the social determinants of addiction or any other aspect of the opioid epidemic.

Naloxone is an opioid receptor antagonist meaning it binds to opioid receptors and reverses or blocks the effects of other opioids. Giving naloxone rapidly reverses the effects of opioid drugs, restoring normal respiration. It can be administered by injection or through a nasal spray.

Source: NIH/NIDA website

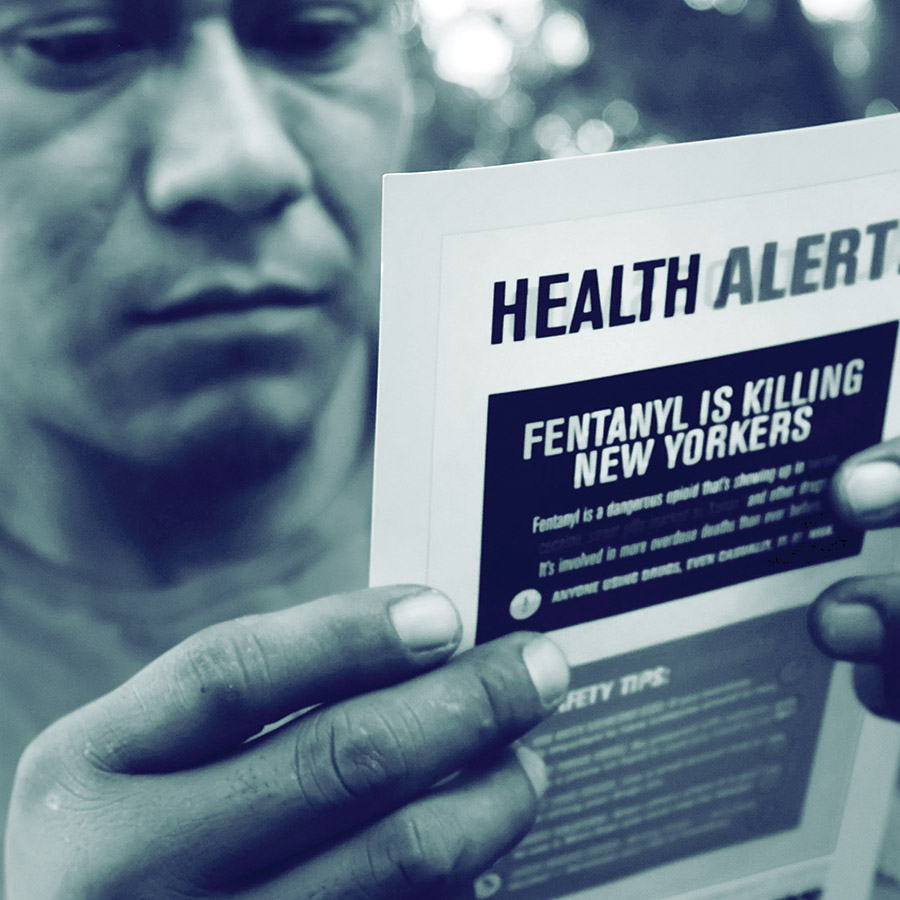

In the Bronx, a heroin user reads an alert on fentanyl before being interviewed by John Jay College of Criminal Justice students as part of a project to interview drug users in order to compile data about overdoses. The students interview their subjects in a park and ask questions about their history of drug use and if they have overdosed. The subjects received a small financial compensation for their participation. (Photo by Spencer Platt/Getty Images).

Prevention: A crucial yet often neglected piece of the puzzle

Given the challenge of countering longstanding opioid use disorder, it makes sense to diagnose it early on or even prevent exposure to opioids in the first place.

“Regrettably,” adds Huang, “supply, especially of fentanyl, has been conflated with the southern border and immigration issues. We need to reframe these, of course, and develop policies that would actually make a difference.”

Identifying those at risk along with early detection of opioid use disorder remain high priorities for the team and, indeed, for all stakeholders seeking solutions to the crisis, most notably the families and patients who are dealing with it directly.

Looking ahead

Since the start of the HEALing Communities Study and CUNY SPH’s New York State-based initiative, communities have designed multiple strategies to implement evidence-based practices, but many challenges remain. Given the associated effects of the COVID-19 pandemic and fentanyl supply, the analysis of the system dynamics model shows a clear challenge to reversing overdose death rates, even with expanded, sustained implementation of evidence-based practices. And prevention is still a work in progress.

Huang is concerned about another feedback loop: if communities succeed in reducing overdose deaths, resources may be shifted away from the opioid crisis in these communities and toward some other public health issue.

“There is no silver bullet for opioid use disorder and its associated overdose and deaths,” says Huang. “This is a massive problem that isn’t going away anytime soon.”