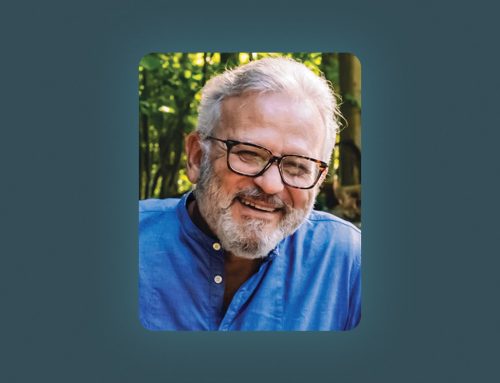

Suzanne McDermott & Heidi Jones

What is the difference between a friend and a boyfriend or girlfriend?

What is love?

What is consent?

What can you do if someone touches you in ways that you don’t want to be touched?

How do you know when it is ok to be sexual with someone else?

These are not the questions of a prying parent. They come from a socialization and sex education curriculum that CUNY SPH researchers are updating and testing on adolescents and young adults with mild to moderate intellectual and developmental disabilities.

Most public-school students in the United States receive “comprehensive” sex education at some point during grades 6-12, and well-documented evidence shows that such education reduces rates of mistimed or unwanted pregnancy and sexually transmitted infections among teens and young adults. But adolescents and young adults with intellectual and developmental disabilities (I/DD)—who are commonly misjudged as being asexual or lacking the ability to acknowledge and discuss sexuality—are less likely than their non-disabled peers to receive it, even though they need it just as much, according to Professor Suzanne McDermott, who is the Co-Principal Investigator with Heidi E. Jones, of a randomized controlled trial of a curriculum for adolescents and young adults with Down syndrome and other types of mild and moderate intellectual and developmental disabilities.

“This population is often left out of sex education in public school,” McDermott says, noting a recent national survey in which only 44% of U.S. public school children with mild I/DD and 16% with moderate to severe I/DD received sex education compared to 48% without disabilities. The sex education they do receive often emphasizes menses and hygiene rather than choices regarding sexuality and fertility, she adds.

Not surprisingly, adolescents and young adults with I/DD often experience worse reproductive health outcomes than their non-disabled peers, are less likely to use contraception, face increased risk of mistimed or unwanted pregnancy and have less access to reproductive health care services, including vaccinations against human papillomavirus (HPV) and cervical cancer screening.

“People with intellectual disabilities can be vulnerable, since they are less likely to believe they can make decisions without the input of others” McDermott says. “The key concepts we plan to address are reciprocal relationships, trust, consent, and safety.”

While many reproductive health brochures and programs are offered to people with I/DD, Jones says that neither she nor McDermott know of any that have been tested for effectiveness using the rigor of a randomized controlled trial.

“Furthermore,” Jones adds, “individuals with I/DD have historically been excluded from randomized controlled trials, which ultimately prevents researchers from identifying true evidence-based interventions for this population.”

McDermott and Jones will be recruiting participants from most of New York state, including New York City, so that the lessons learned can be generalized to adolescents and young adults in both urban and rural locations.

The curriculum being tested uses individualized counseling, coaching and support related to social relationships and sexuality. The comparison arm of the randomized controlled trial will be a healthy eating and exercise program.

McDermott designed the curriculum, called STEPS, in the early 1990s while in South Carolina. STEPS so notably improved reproductive health knowledge and contraceptive use among female participants that it became a Medicaid reimbursable service that now reaches thousands of individuals with I/DD through the state’s Department of Disabilities and Special Needs provider network. A published program evaluation found that it improved knowledge, however, no randomized controlled trial has evaluated its efficacy on behavior change.

“We know the curriculum increases knowledge,” says McDermott. “We need to know if it changes behavior. The proposed project, to our knowledge, is the first randomized controlled trial of a sex education curriculum designed for adolescents and young adults with I/DD.”

The trial will enroll 856 adolescent and young adults of all genders aged 16-27 years, with mild to moderate I/DD who receive services from disability providers in four of the five developmental disabilities regions of the New York State Office of People with Developmental Disabilities. The researchers will stratify participants by severity of disability, region, gender, and age (16-22, 23-27). Half of the participants will receive the updated socialization and sex education curriculum, while the other half will receive a previously evaluated intervention on physical exercise and nutrition. Both interventions will occur over six weeks, and reproductive, socialization and sex education health and related behaviors will be compared at baseline (prior to intervention) to month 12 (approximately 10 months after completing the intervention).

The curriculum addresses topics, such as self-esteem; agency and personal relationships; decision making; bodily functions and hygiene; understanding and proper use of family planning and health care consumerism through discussion and open-ended questions, such as: What does it mean to make your own decisions? How do you know who you can trust? What is safe sex? “Understanding and being able to discuss these issues is vital for people with I/DD, who are easily exploited,” McDermott says.

“This population is easily taken advantage of because they’ve learned to depend on others to make decisions,” she adds, referring to a study that revealed widespread abuse among males and females: 61.9% of males and 58.2% of females reported childhood abuse, and 63.7% of males and 68.2% of females reported abuse during adulthood. Thus, they hope to learn if the curriculum can help people increase the size of their social network by helping them develop the social skills it takes to be a friend.

“People with I/DD are concrete learners,” McDermott says. “In this program, we’re explaining things in ways that are concrete and clear so that individuals with these disabilities can make good decisions.”

To promote the concept of sexual safety, the curriculum covers informed consent, which can be confusing to people with I/DD.

“If you ask someone in this population if they’ve had sex, they may say ‘yes’ because they’ve kissed their boyfriend or girlfriend,” she says. “So, you try to get them to tell you what happened by asking more questions, like ‘Where did you kiss your boyfriend/girlfriend? Were you alone in the room? Did you touch him/her? Did s/he touch you? Did you want it?’ ”

Through the trial, the researchers hope to test the curriculum’s effectiveness in improving use of contraception and protection against sexually transmitted infections, HPV vaccination status and receipt of sex and age-appropriate preventive health screening.

“One of the simplest behavior changes we hope to increase is that young people with I/DD visit a healthcare provider for a reproductive health evaluation whether they’re sexually active or not, which most people don’t do,” McDermott says.

Proof that the intervention significantly increases access to reproductive health services will give the researchers the foundation they need to develop best practices for socialization and sex education for adolescents and young adults with I/DD, McDermott adds.

“People with intellectual disabilities can have a good healthy life, and this is one way to make that happen.”