With persistent vaccine resistance across the U.S. and protests against vaccine mandates both at home and abroad, there is a prevailing understanding among those who believe in immunization against COVID-19 that everyone who has not gotten vaccinated is strongly opposed to it.

But according to Chris Palmedo, a professor of communications at CUNY SPH, it is not quite so simple. In the spring of 2021, Palmedo led in-depth interviews with people who were holding off on getting the COVID-19 vaccine. While affirming the enormous and critical public health benefits of vaccination, Palmedo says that treating the unvaccinated as if they are all extremists has led to communication strategies that fail to acknowledge the institutional mistrust that is often at the root of people’s hesitancy.

“The folks we interviewed were smart, they cared about health, respected the virus, and were not highly conspiratorially driven, thinking the virus is a hoax or a scam,” says Palmedo, who with his team published the interview results in December in American Behavioral Scientist. “Vaccine hesitancy was the tip of the iceberg. Hidden beneath the tip of that iceberg was genuine distrust of institutions, including the media, the government, and the healthcare system—often based on their own experiences.”

‘Trust that wasn’t there to begin with’

Palmedo is a faculty fellow with CONVINCE USA—which stands for COVID-19 New Vaccine Information, Communication and Engagement, an initiative at CUNY SPH dedicated to building support for COVID-19 immunization and the science behind it.

When the vaccine rollout was in its infancy in 2021, he and his team began to interview individuals who wanted to “wait and see” before they got the COVID-19 vaccine, a term they adopted from Kaiser Family Foundation, which has done polling on vaccination views through most of the pandemic. Through a survey, the team recruited 30 participants who indicated they might get vaccinated someday but weren’t ready to do so yet. Participants were paid $60 to take part in a 45-to-90-minute in-depth interview about their thinking around the COVID-19 vaccine, how they seek information, their general attitudes toward vaccination, and their pre-pandemic experiences with the healthcare system.

Several key themes emerged, according to Palmedo. The first was that the information people were getting during the pandemic was confusing and conflicting—particularly the different messages from different levels of government.

Palmedo says this can be understood in context of the state of the media ecosystem, particularly fracturing media outlets and audiences; the speed at which misinformation is spread; “echo chambers,” in which people spend time in social or other digital media spaces that amplify their existing views; and the two-way nature of social media, which provides more ability to question official sources. Because people are flooded with information, they are more likely to focus on media that is consistent with what they already believe.

Chris Palmedo

Lauren Rauh

One of the most cited reasons for mistrust was the government’s change in its masking recommendations early in the pandemic. Lauren Rauh, senior program manager of CONVINCE USA who led the interviews for the study, believes people would have been less focused on the changing guidance around masking if there were not already such low levels of trust among Americans in their institutions.

“It’s not so much that trust was eroding, but that it wasn’t there to begin with,” she says. Polling organizations like Gallup and Pew Research Center have consistently found low levels of trust in American institutions, and those levels have dipped even more in the more recent phases of the pandemic.

Palmedo notes that other democracies are grappling with similar issues, even if the U.S. has a particularly high level of institutional mistrust.

Another frequently mentioned issue in interviews was how people’s race affected their experience with the healthcare system. One participant of color recounted the story of a nurse who didn’t believe her when she said she was in pain and wouldn’t prescribe medication. Reporting from the Association of American Medical Colleges and other academic research has found that Black patients are consistently under-treated for pain.

“Racism clearly is an issue in healthcare today,” says Palmedo. “If you were treated poorly and the medical system is now telling you to get vaccinated, your past experiences could very well make you question it. Our interviews weren’t the first place that found this, but they certainly confirmed it.”

Economic inequality was also a factor. Some participants expressed that the vaccine was meant for wealthier people, who were much more likely to need it for travel and could afford treatments and time off work if there were side effects.

Their hesitancy didn’t mean participants weren’t health-conscious and concerned about catching the virus. But they were skeptical that the vaccines would protect them, even when—and sometimes because—they had health conditions, like chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.

“They were hyper vigilant about protecting themselves from COVID-19,” says Rauh. “They were cleaning with bleach, were still wiping down groceries, masking even when it wasn’t mandated. What was surprising to me was that the vaccine was not seen as protective, but as potentially jeopardizing their health.”

A few participants said that their doctors had even advised against getting the vaccine, at least until more was known about it in relation to their specific health concerns.

Communication that helps

The study team emphasizes that these issues of deep mistrust cannot be fixed by communications alone.

“While there are some clear communication recommendations resulting from this study, the work needed to rebuild trust will be a long journey, and one we will continue here at CUNY SPH and CONVINCE,” says Scott Ratzan, executive Director of CONVINCE USA, distinguished lecturer at CUNY SPH, and member of the study team.

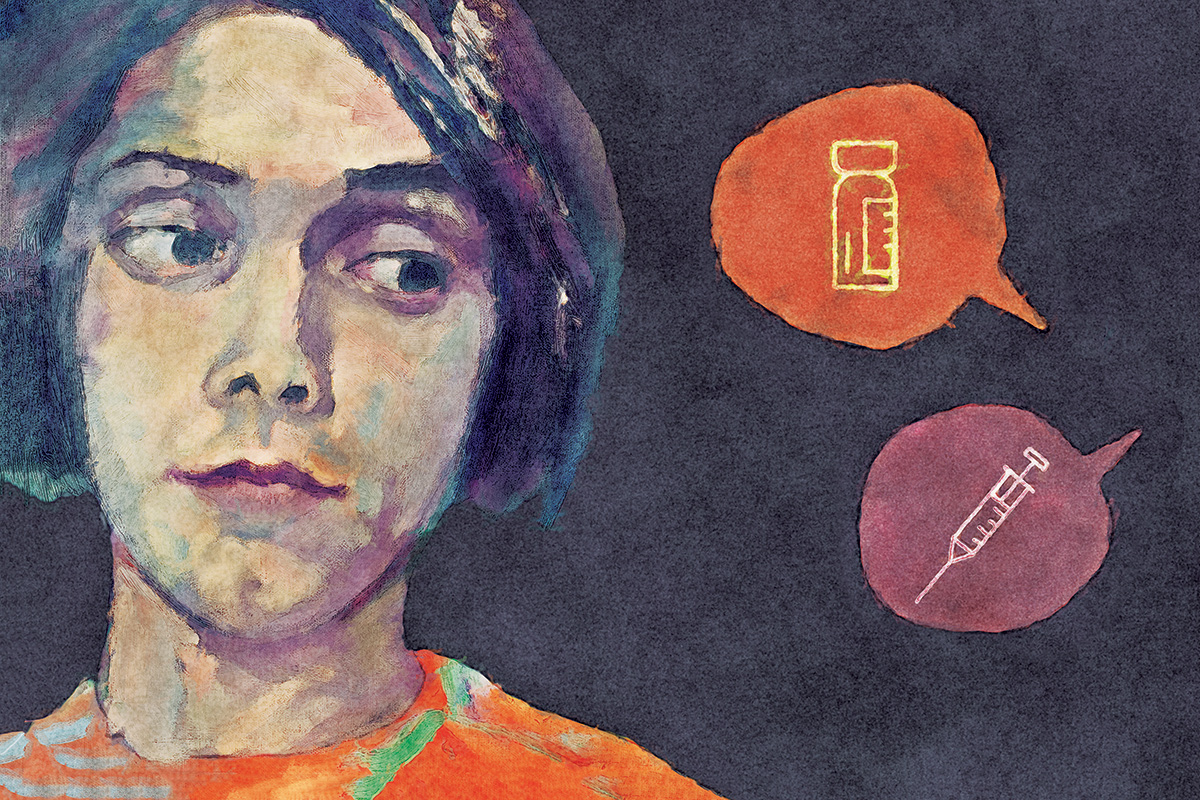

But there are communications strategies that can make a difference. An important implication of the study is that officials should avoid communicating health guidelines as a directive, exhortation, or insult. Palmedo points to when French President Emmanuel Macron said he wanted to “piss off” the unvaccinated, as well as other insulting language that has been present in every-day communication around the vaccines.

“People don’t want to be insulted,” says Palmedo. “You hear things like ‘If these stupid anti-vaxxers just got vaccinated we would be able to get on with our lives.’ Those feelings are understandable from a progress perspective, but the fact of the matter is they don’t work.”

More effective is what Palmedo calls “empathetic communication,” which involves listening to people and acknowledging their concerns, rather than lecturing or labeling people’s questions as unintelligent.

One example is United Airlines, which has done several things right. They acknowledged that some disagreed with their policy to mandate vaccines for employees. They consistently emphasized they were requiring vaccination for everyone’s safety. They also shared numbers that showed the efforts were working in lowering case numbers and deaths, including a 100-times-reduced hospitalization rate compared to the general U.S. population after the vaccine requirement went into effect. It’s also important to communicate that mandates are issued reluctantly, and are “never anything we should enjoy doing,” says Palmedo.

He also suggests identifying points all sides agree upon, such as that everyone deserves to live a healthy life, rather than statements that people disagree with and that will make them defensive.

Finally, it’s important to identify trusted messengers in communities who can respond to people’s concerns while promoting vaccination, like faith organizations, local clinics, or direct service organizations.

“These organizations are entrenched in communities, and impactful in people’s lives,” says Rauh. “They spend a lot of time listening to people and responding to their needs. Larger institutions can learn a lot from how trust is built at the community-level.”

Looking ahead

None of this work is easy, Palmedo acknowledges: “We’re not going to change people’s views overnight but there is a movable middle, and respect for the people in this group—addressing their questions and providing evidence-based responses will take time,” he says. “So much of good communication takes a little more work and a little more time.”

With COVID-19 receding at least for now, the team is currently doing work to help “prep for the next time this happens,” says Palmedo. They are working to develop a survey tool called the vaccine trust gauge to measure individual-level trust in vaccination and help communicators including health care providers, public health practitioners, and community-based workforces “meet people where they are” in their vaccine decision-making. They’re also working with the New York City Pandemic Response Institute, in which CUNY SPH is a key partner with Columbia University, to investigate how trust in the public health infrastructure and response is built, and how people make health decisions more broadly.

And whether or not the pandemic is mostly behind us, says Palmedo, the issue of mistrust of institutions will continue to frame society’s most significant challenges.

“Clearly there will be more challenges in the future, and they may be related to another pandemic, or another emergency, like a natural disaster,” says Palmedo. “A lot of the same issues will come up, including distrust based on class, race, and media consumption. We need to explore this issue as thoughtfully as possible now, so we’re more prepared then.”

CRITICAL COMMUNICATION

This poster with a charged tone aimed at the unvaccinated embodies the hard-line communications strategy many frustrated officials have adopted since the pandemic began. The study team’s work indicates such an approach is ineffective. Credit: Chamomile Tea Party