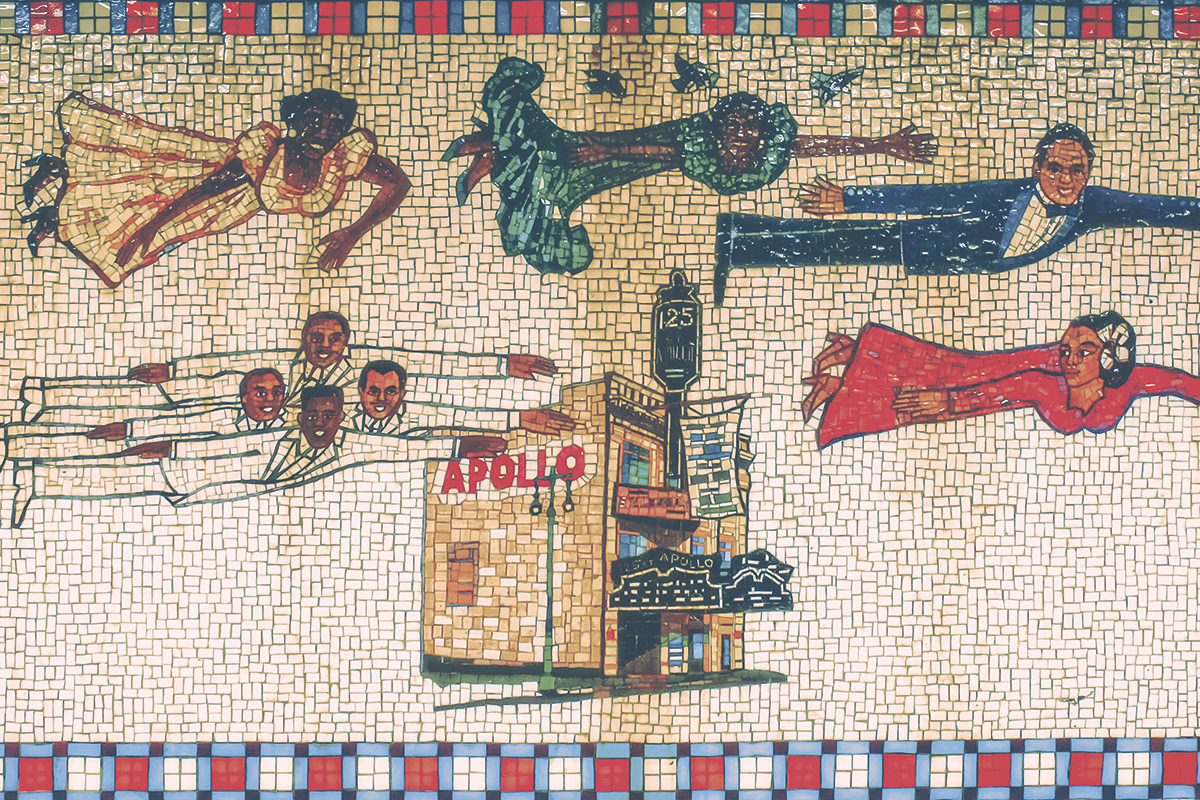

A Harlem subway station mosaic on the platform wall at 125th Street. The strength and heritage represented in the artwork echoes today through the community’s commitment to the Harlem Strong project. Art by Faith Ringgold, Flying Home: Harlem Heroes and Heroines (Downtown and Uptown), 1996. Glass mosaic on platform walls. Image credit: Troy Tolley

At the beginning of the pandemic, Malcolm A. Punter noticed mounting stress among the staff at Harlem Congregations for Community Improvement (HCCI).

The counselors and case managers who were helping people in need had an additional responsibility—to protect their own physical and mental health amid extraordinary grief.

Two years later, an awareness of debilitating stress, anxiety, depression, and trauma throughout the community has led to Harlem Strong, an initiative of CUNY SPH, to integrate mental health screening with existing touchpoints of care.

“COVID-19 exacerbated and exposed the glaring gap between the services people need for mental health care and what they are getting,” says Victoria Ngo, associate professor and director of CUNY SPH’s Center for Innovation in Mental Health (CIMH). “That increased awareness created the momentum for us to do something about it, to pull together the resources, to seek the funds to address these needs and at this scale. That’s what has given birth to Harlem Strong.”

Rather than a single program, the Harlem Strong Initiative is a cooperative of organizations, individuals, resources, interventions, and trainings to identify signs of compromised mental health and increase the community’s capacity to provide care. The initiative is coordinated through the CIMH and supported by nearly $2.5 million in grants from the National Institutes of Health and the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation over the next five years.

“The goal for both of these grants is system transformation,” Ngo says. “We don’t want to make incremental changes in the community and the system. We want to leverage the strengths that are already in Harlem, to rethink how services are provided and how we can better reach community and support community.”

Deborah A. Levine, a clinical psychiatric social worker and director of another CUNY program, the Harlem Health Initiative, hears painful conversations about mental health concerns in the neighborhood right outside the university’s doors. Harlem Strong, she says, will link the people who routinely take the pulse of the community—case managers, health workers, and trusted clergy—to increase the reach of mental health services and minimize barriers to care.

“Harlemites are experts of their own lives,” Levine says. “The lived experiences and expertise of Harlem’s community stakeholders and faith leaders are the backbone of the Harlem Strong project.”

Trust-building is accomplished through institutions that serve the population directly, says Punter, including the more than a thousand houses of worship in Harlem. “Instead of going to a mental health facility, someone might go to their trusted advocates, a pastor or imam or rabbi and lay their burdens on those folks who may not be qualified to help,” he says. “That’s the gap we’re trying to fill by creating a partnership for training, not to try to supplant them.”

Malcolm A. Punter

Deborah A. Levine

Why now?

In 2020 and 2021, at the height of the pandemic, researchers at CUNY SPH found high rates of job, housing, and food insecurity coupled with depression and anxiety rates (35-45 percent) for Black and Latino Americans in New York City. These pandemic-related threats to mental health of Harlemites, coupled with historically poor access to quality mental health care for ethnic minorities, perpetuate poor mental health outcomes.

The pandemic further stressed people, especially those with previous health conditions and front-line service workers in restaurants or delivery businesses. “They’re at greater risk, but if they don’t work, they can’t feed their families,” Ngo says. Add to that the strain of living in small apartments without privacy for a child to do homework or a parent to make work calls.

“All of these very pressing, very real-world problems are impacting work and school and finances,” Ngo says. “That just adds to the mental health risk. If your functioning is impaired and you can’t work, there’s a domino effect. It can cripple a community.”

A work in progress

Two groups are tasked with keeping the initiative on track. The 12-member Harlem Strong community advisory board, chaired by HCCI Executive Director Punter and representing the community, medical, and political fields, held its first meeting earlier this spring. A larger planning council of community stakeholders also helps steer the initiative. Programmatic goals include mapping out community-based organizations and the services they provide, scheduling neighborhood focus groups and surveys, devising trainings for a large cohort of mental health screeners, and developing ancillary service programs to help residents with financial literacy and housing assistance.

The initiative will support the development of a technology platform to provide training, a searchable directory to link clients to care, resources for mental health screening, and self-help management tools. One of the goals of the platform will be to use crowdsourcing techniques to identify technology tools that would be most beneficial for addressing implementation gaps, which may include electronic referral systems, consumer-facing mental health apps, as well as other client management systems for community-based organizations.

While Ngo and her colleagues will evaluate the program’s ongoing impact and cost effectiveness, she points out, “The best investment is to focus on managing and supporting people to have the skills to deal with stressors that will continue to impact the community.”

Healthfirst, one of New York’s largest not-for-profit health insurers that helped write the funding grants, will identify metrics and strategies for continuous improvement and sustainability. That includes providing data management and analyzing patterns of utilization and care among the 16 or so primary health care practices working with Harlem Strong. Reimbursement claims can be tracked, along with pharmacy use, requests for diagnostic tests, and follow-up visits. “You rarely see these things tracked longitudinally,” says Susan J. Beane, Healthfirst vice president and executive medical director. “I’m excited to see this play out, how the pieces come together and change things over time.”

“Healthfirst will also assess health care providers for biases that contribute to inequitable mental health care, identify how a medical practice responds to patients with mental health needs, and the likelihood of patients to approach a practice for help,” Beane says. Healthfirst will provide different modes of clinical training, including group learning and web-based conferences, to screen patients and know when to make a referral to a specialist.

Training provided by additional partners, including HCCI, is scheduled to begin by late summer 2022 and will extend to case managers, faith leaders, and people committed to learning the program and providing emotional or therapeutic support in one way or another, Ngo says.

Susan J. Beane

Victoria Ngo

Malcolm X Blvd at 125th Street in Harlem. Image credit: Adrien Leguay.

For example, under this system of task sharing, a case manager helping a woman find housing might notice that she is highly stressed and likely to abandon what can be a long process. With training, the case manager could screen the applicant for depression and anxiety. “They can let them know that many people are struggling during the pandemic,” Ngo says. “They can explain what depression is and offer ways to help,” including referrals to treatment in the neighborhood and offer to follow up on their care.

Quality outcomes will be tracked and shared in close to real time to see what works and what doesn’t, Ngo says. At the 6 and 12-month marks, researchers will evaluate the impact of Harlem Strong on mental health, social risk, and the outcome of receiving care. At the 6, 12, and 24-month marks, researchers will measure implementation outcomes at housing developments and primary care settings, including provider knowledge, attitudes, skills related to mental health literacy, screening, referral, and coordination of care.

Researchers will also assess the cost-effectiveness of Harlem Strong’s neighborhood-based community collaborative care model, where coalition building is facilitated, and implementation challenges are resolved through the network. A control group will receive the same training for integrating mental health care to determine whether investments should be made to neighborhood-based community collaboratives to increase uptake of mental health task sharing.

The network of organizations created by Harlem Strong breaks down the siloed, fragmented approach to health care. “And when you combine that with social services and housing it’s crazy making,” Ngo says. “If navigating the health care system is hard for people with an education and economic stability, what happens to people who are struggling with the English language? How are they getting help?” Ngo asks. “They’re not.”

Equity in health care

Data clearly show that length of life differs by neighborhood, ethnicity, language, culture, and gender, according to Beane, who was born in Harlem and grew up in the South Bronx. But the confluence of events around the pandemic and the racial unrest after the death of George Floyd prompted providers “to ask out loud if can we do better,” she says. “Harlem has always responded to the needs of its residents. If we can change the trajectory of health for people who are living the legacy of struggle that is Harlem, we can take the lessons learned almost anywhere.”

Harlem Strong draws on Ngo’s experience over the last decade developing a similar task-sharing approach in her native Vietnam. Under that model, primary care providers screen patients for depression. Ngo also helped create a complementary program that repackages depression care with small loans to help women with depression through supporting their livelihood. “Most of our patients are so poor … their priority is what to eat tonight, not is their depression treated,” she said at the time.

Harlem Strong involves a higher level of community engagement and the development of a network across organizations. It’s also a continuation of CUNY SPH’s partnerships with New York City, including the Department of Health, Health and Hospitals Corporation, and other agencies that have the potential to scale the program to more neighborhoods.

Ultimately, Ngo hopes Harlem Strong will be sustainable and result in a system that’s easier to navigate. Now, if someone gets a referral to a therapy program without an opening, they will likely fall through the cracks. The coalition will provide opportunities to break down the silos, help providers and organizations learn about one another’s programs, and support a coordinated referral system that should plug those holes.

“We’re working to figure out how the consumer journeys through different service systems, like housing, community-based service organizations, primary care, behavioral health, and where they struggle,” Ngo says.

To ensure that members of the community have the loudest voice at the table, Levine and Punter say, they will be asked what they lack now and how health care can best be delivered to them. Whether in the form of surveys or interviews, Harlem Strong needs to hear from burned-out care givers, elderly members of congregations who are too fearful to leave their homes, and owners of failed businesses facing poverty instead of the middle-class life they dreamed of.

“We’re asking people with anxiety, depression, insufficient income, and elders who are homebound to help with our survey to come up with a massive plan,” Punter says. “But that’s five years down the line and now they’re sitting at home and can’t even eat. We want to help people right now.”

The partners in Harlem Strong understand that the program will intentionally take time to develop and assess. Shortcuts just aren’t acceptable.

“Our initiative may provide the framework that can be built upon in the future,” Punter says. “That’s the purpose of scientific inquiry. You don’t get to solve the problem in one swoop. I just hope to provide a small contribution that could become a breakthrough.”